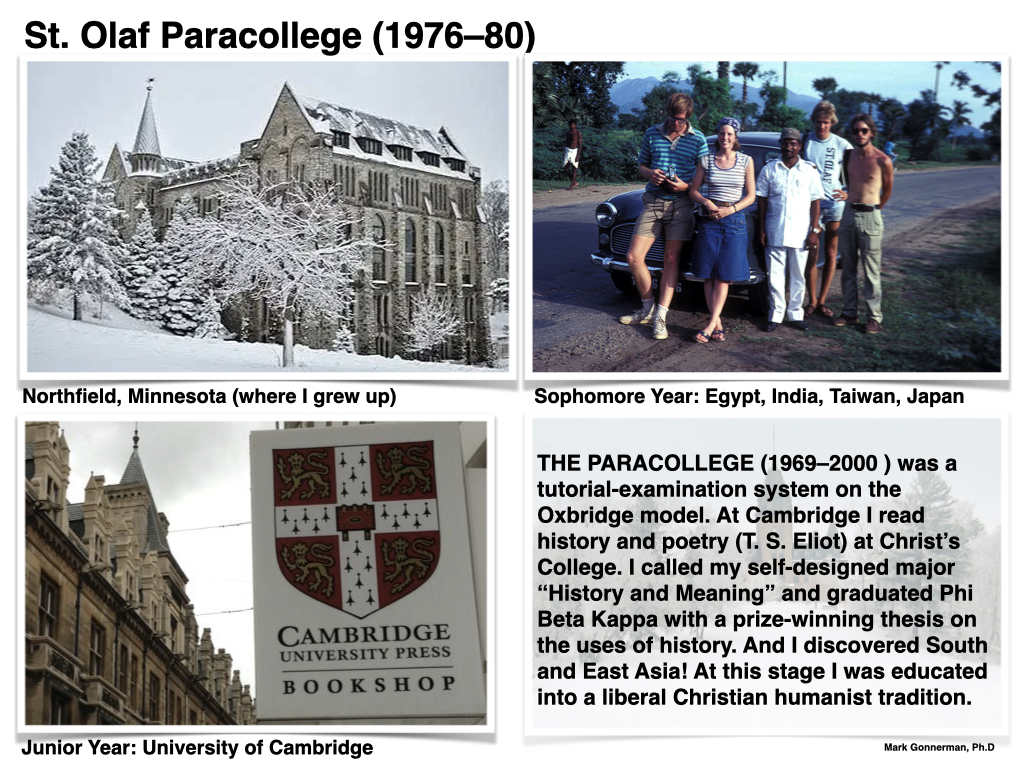

When launched from the paradise of the Paracollege at St. Olaf in the spring of 1980, I carried my Phi Beta Kappa key back to Japan and joined for three years a peace education project out of Hiroshima. I was first there while on the Global travel-study program to Rome, Cairo, Jerusalem, Bangalore, Kathmandu, Hong Kong, Taipei, and Kyoto at the start of my sophomore year.

From Hiroshima I headed to Harvard for the M.Div. degree with coursework in anthropology and East Asian studies, where I was as a teaching fellow for two of my three Cambridge years.

Then to Stanford for the doctorate in religious studies, completed with a dissertation that drew on my deep dive into the journals of the pioneering Buddhist poet Gary Snyder (b. 1930 and still at home in the Sierra Nevada), a key figure in the transmission of Zen from Kyoto to California.

During my studies, I conjured the yearlong Mountains and Rivers Workshop at the Stanford Humanities Center, an effort to turn the multiversity into a university again, if only for a moment. You may learn more about this in my book, A Sense of the Whole: Reading Gary Snyder’s Mountains and Rivers Without End (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2015).

I stayed on at Stanford as a lecturer and founding director of high-profile Aurora Forum conversations in person and on public radio with people who turn vision into action for positive social change. This was an exercise in community building that drew on my field education in divinity school to break down barriers between academic worlds and the street, where one learns to learn from experience.

After 24 years at Stanford plus four as a professor at the former Institute of Transpersonal Psychology in Palo Alto, I became for three terms prior to the pandemic a visiting professor of American literature at Hunan University in the People’s Republic of China. This campus on the west bank of the Xiang River in Changsha is home to a 1,000-year-old Confucian academy at the base of Yuelu Mountain. Hunan University students and faculty are fun, intellectually curious, and savvy in ways that made my too-brief tenure there a highlight of my peripatetic life of teaching and learning.

I share these reminiscences in part because I mourn the passing of the Paracollege (1969–2000). Here I was welcomed into a tutorial-examination system on the Oxbridge model, which prepared me well for junior-year adventures at the University of Cambridge. Paracollege students were encouraged to build a solid foundation by first learning how the various domains of knowledge are interrelated. We then carved out a concentration for our studies and produced a thesis or senior project. We did not receive letter grades, but faculty advisors in our one-on-one tutorials and small-group seminars provided regular narrative summaries of each student’s growth. Unfortunately, administrators at the start of the new millennium determined that this age-old approach to the formation of educated persons is not cost-effective in monetary terms, thereby downplaying the equal if not greater value of the social and cultural capital that makes life worth living, especially when shared through more personal pedagogical processes.

Last summer, I found my bookish self sitting daily at a table beneath a coast live oak in a privately owned public space not far from my house in San José. In this peaceful soundscape of falling water, birdsong, and muted voices of people of all ages strolling by, I read from start to finish Iain McGilchrist’s The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World (Perspectiva Press, 2021).

This tome in two volumes has great explanatory power with regard to many of the current predicaments that suggest we humans are rapidly losing our way. All is not yet lost as the author reminds us of cultural resources and insights we must draw on going forward. I am especially impressed by Dr. McGilchrist’s effort to begin balancing Western and Asian perspectives on the baseline realities that sustain our lives.

So I end here by commending to you, dear reader, The Matter with Things as the virtuosic contribution of a large-hearted, Oxford-educated, polymath psychiatrist who represents the old, vital, and still-accessible (if you know where to look) tradition of learning in the artes liberales, the arts that liberate people into the kind of awareness that will cut through so much noise. As I came to appreciate the depth, breadth, and integrity of McGilchrist’s profoundly humanistic inquiry, I felt much gratitude for my four years in the Paracollege and all that is possible when love of learning becomes the guide of life.